Editor’s Note (December 2025):

This article serves as a clarification and refinement of our previous discussions on the so-called “pagan roots” of Christmas. In light of updated research, including the work of Christian apologist Wesley Huff and broader historical scholarship, we affirm that while some seasonal customs may have pre-Christian analogs, the holidays of Christmas and Easter are not pagan in origin or practice. This aligns with our 2023 position that these are distinctively Christian observances, grounded in the birth and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

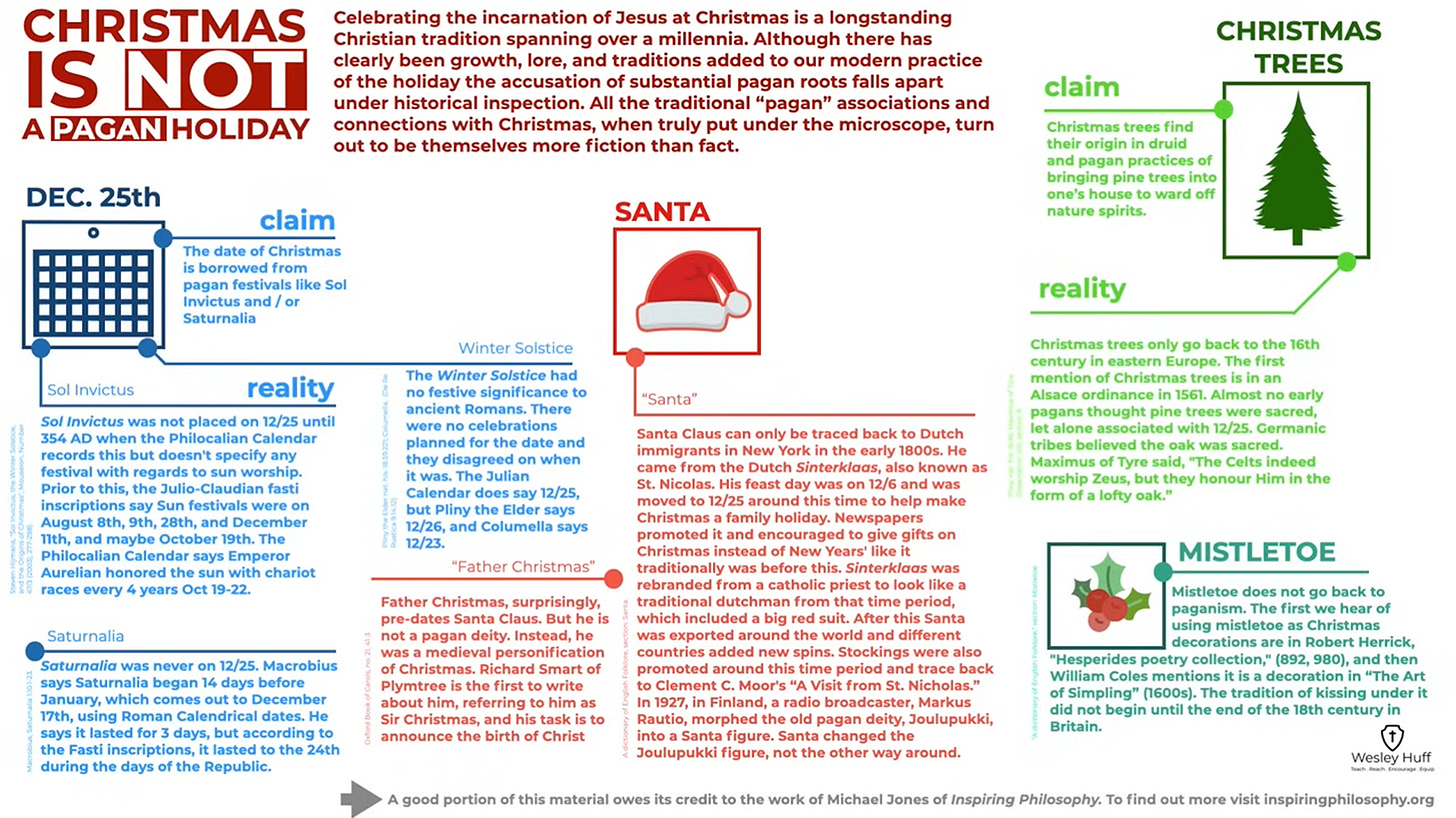

Every December, a familiar chorus rings out across the internet: “Christmas is pagan.” This claim (often delivered with a generous helping of YouTube conspiracy theories, pseudo-history, or fringe theology) insists that everything from Christmas trees to the very date of December 25 is rooted in pagan idolatry.

While it’s true that certain pagan cultures celebrated festivals near the winter solstice, the idea that Christmas itself is a direct repackaging of those festivals doesn’t hold up to serious historical scrutiny. As we’ve previously stated, and now further reaffirm with new data and analysis, the holidays of Christmas and Easter are not pagan in origin or meaning. They are Christian celebrations that commemorate real, history-anchored events: the birth and resurrection of Jesus Christ. Much of what is claimed about the “pagan roots” of Christmas is either exaggerated, misapplied, or outright fabricated. It’s time we stop surrendering Christmas to bad history.

The Pagan Parallel Fallacy

Critics often point to superficial similarities between Christian and pagan practices (trees, lights, gift-giving, seasonal feasts) and conclude that one must have borrowed from the other. This reasoning, however, is deeply flawed.

Parallels do not prove origins. Just because two practices resemble one another doesn’t mean one caused the other. Pagans lit candles in winter. So did early Christians. That doesn’t make candlelight inherently pagan. Pagans gave gifts. So did the Magi.

To claim that Christian practices are therefore pagan is to commit the “parallelomania” fallacy. This is a term coined by scholars to describe the tendency to overstate the influence of one tradition on another based on superficial similarities.

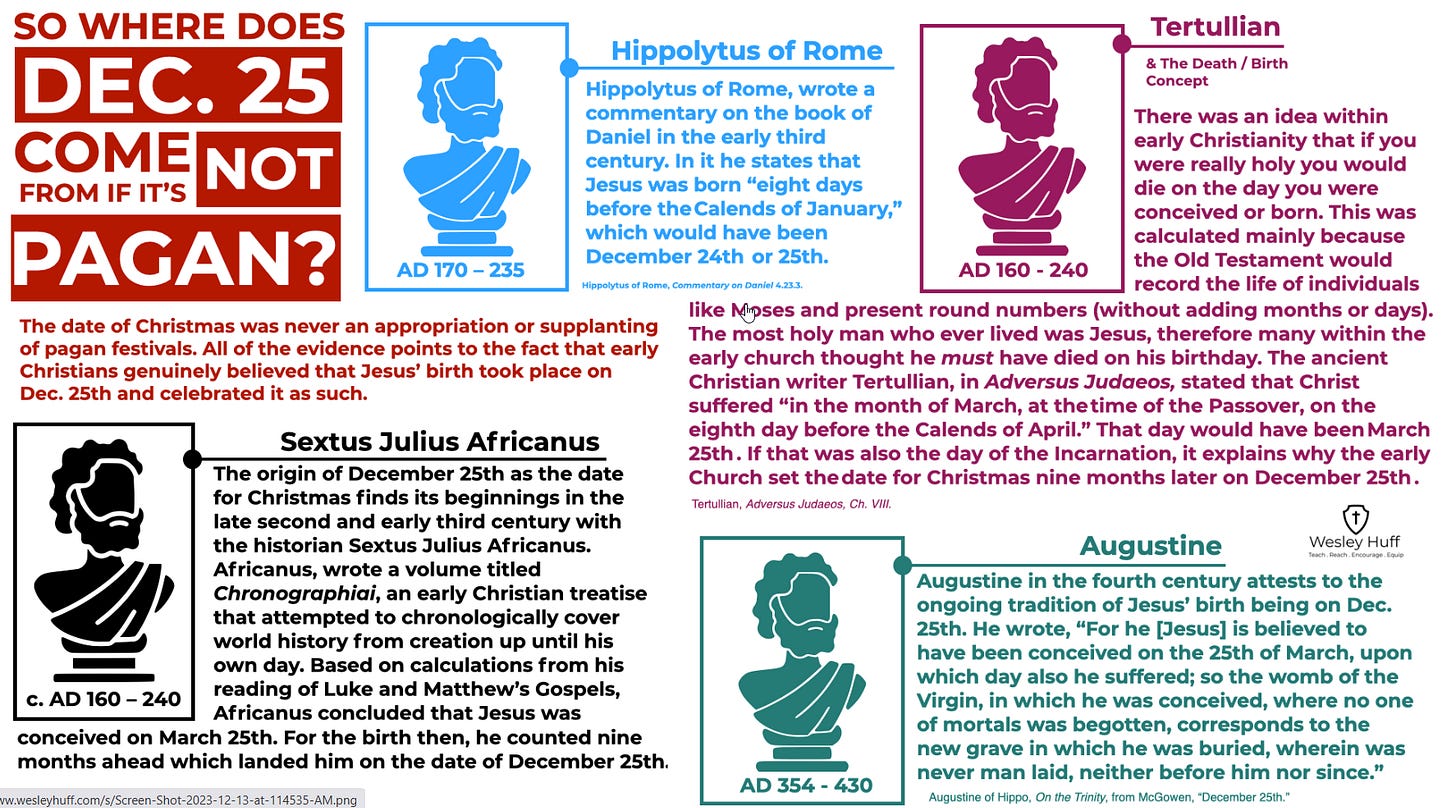

December 25: Christian Before It Was Pagan?

A popular accusation is that December 25 was stolen from Sol Invictus, the Roman sun god’s feast day. But the historical evidence flips this narrative.

The first recorded reference to December 25 as Jesus’ birthday appears in the early 3rd century and before Sol Invictus was formally linked to that date. Roman Emperor Aurelian’s declaration of December 25 as the feast of the Unconquered Sun (Sol Invictus) came in AD 274, possibly in response to the rising popularity of the Christian faith, not the other way around.

Moreover, early Christians had theological reasons for choosing this date. Based on the belief that prophets died on the same date they were conceived, and dating the crucifixion to March 25, early theologians counted forward nine months to December 25 for the birth of Christ. That might not be airtight science, but it certainly wasn’t about worshiping Saturn or Mithras.

The Tree Isn’t an Idol

Next up in the list of charges: the Christmas tree. Opponents of the holiday often quote Jeremiah 10, which condemns decorating trees as idols. But a plain reading of that passage shows it’s about carved wooden idols, not living evergreen trees strung with lights. The passage describes craftsmen cutting wood, shaping it, and adorning it as a false god, which has nothing to do with the modern tradition of decorating a Christmas tree.

Historically, the modern Christmas tree has Christian origins in medieval paradise plays, where trees symbolized the Garden of Eden and the coming redemption. Later, German Protestants used evergreens to illustrate eternal life. If anything, the tree became a symbol of Christian hope and not a remnant of druidic tree worship.

What Scripture Actually Says About Celebrations

Another common objection is that the Bible doesn’t command us to celebrate Jesus’ birth, so we shouldn’t do it. That logic would also rule out Thanksgiving, weddings, birthdays, and national days of prayer.

In fact, Jesus Himself participated in Hanukkah (the Feast of Dedication), a holiday not instituted in the Old Testament but rooted in Jewish history. Clearly, a celebration doesn’t have to be divinely commanded to be meaningful or valid.

The Apostle Paul wrote in Colossians 2:16, “Let no one pass judgment on you… with regard to a festival or a new moon or a Sabbath.” Romans 14 affirms that believers may esteem one day as special or treat every day the same. Liberty of conscience, not legalistic suspicion, should guide Christians on this issue.

Christian Liberty, Not Pagan Panic

At bottom, the annual campaign against Christmas often says more about modern conspiracy culture than it does about early church history. Yes, commercialization is a real concern. Yes, Christians should avoid syncretism. But there’s no solid evidence that Christmas was born in paganism. There is ample evidence, on the other hand, that it was forged in Christian reflection on the incarnation, the astonishing claim that the Word became flesh and dwelt among us.

If you’re personally uncomfortable celebrating Christmas, you don’t have to. But let’s stop pretending that December 25 is a Trojan horse for Babylonian sun gods. It isn’t. It’s a day Christians set aside to honor the moment in history when heaven invaded earth and nothing has been the same since.